Common Questions

I’m new to working with children with disabilities – what do I need to do?

Suggestions:

- Start with the realization that children with disabilities are children first. All children respond in different ways, and need to be approached individually.

- Plan to spend additional time preparing for and investigating cases. Gather as much information about the child as you can from key people in their life.

- Talk to the right people. If the child is old enough and able to respond, ask them if there is anyone in particular they want to be involved. If not, the best resources will be the child, the non-abusive family members or care providers, the child’s teacher, and others who know the child well.

- Do your research. Get to know basic information about the child's disability, and how it may impact your interactions with the child and the investigation. Also consider what the child experienced, how they processed what they experienced, and how they might communicate.

- Know when to get help. If you feel you cannot provide adequate services for this child, explore whether or not another staff member can assist or conduct the interview (U.S. Department of Justice).

- Persevere. Cases of abuse against children with disabilities can be won.

- Give the child time and space to get to know you.

How can I prove this child is a competent witness?

Suggestions:

- Understand the child’s individual needs. Children with certain disabilities may have difficulty reporting abuse. The abuse itself can lead to anxiety disorders, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, and emotional disorders, all of which can impact the ability of children to focus and communicate what happened, according to Cristina Rainville

- Take time. Meet with treating therapists, teachers, special educators, interpreters, and child care providers.

- Document any behavior changes that might corroborate abuse, the best ways to communicate with the child, and indications that the child can tell the truth and also knows the difference between what is real and what is not real.

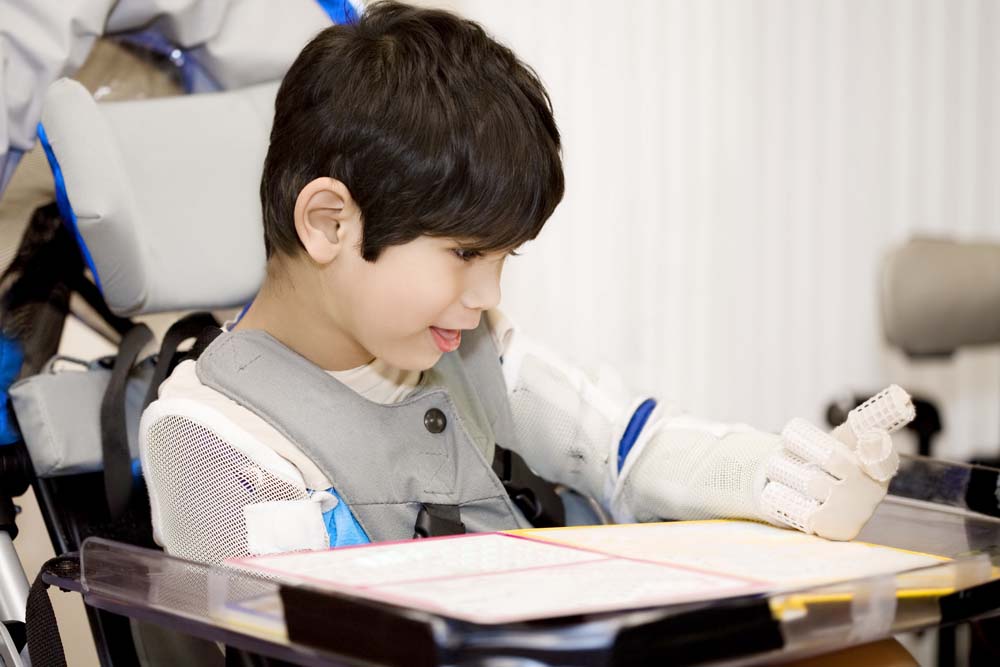

- Focus on communication. All children can communicate in some fashion, whether it is through behavior; indicating yes or no to questions (shaking or nodding head, blinking eyes, thumbs up or down, or tapping a pencil); showing what happened through drawing or using anatomically correct dolls; texting; or using a communication device.

One father of a child with Autism Spectrum Disorder knows that when his son flaps his hands and spins, he’s happy. When he bites his hand, he’s bored. He knows that when his son repeats things, he’s not being sarcastic—he just doesn’t know what to say. Knowing what these behaviors mean can help with the investigation and the interview. ( J. Roppolo, personal communication, May 24, 2014.)

I’m working with a child who is becoming withdrawn and doesn’t seem to want to communicate. What can I do?

Suggestions:

- All behavior is an attempt to communicate. Ask parents, caregivers, family members, or teachers to interpret the child’s behaviors.

- Refuse to give up easily. The more silent or withdrawn a child is, the more likely it is that something happened to them, or that they have lost trust in adults. Keep showing up with a positive attitude and seek some kind of common ground.

- Be patient. It may not be easy to see that you are making progress. However, through your calm, consistent, and kind interactions you are showing the child that they can trust you, that you are open and willing to help, and that you are there to listen to them.

- Keep trying. One legal advocate worked with a girl with a disability for seven months. The first three visits, she refused to see him. Then she’d see him but sit with her arms closed. He kept showing up until she talked, and once she started talking, she became very communicative. (I. Spechler, personal communication, February 4, 2014).

How do I work with children who do not communicate with words?

Suggestions:

Presume competence

- Always presume competence. Every child with a disability is different, so approach every child with curiosity and an open mind.

- Every child and youth has some way to communicate, even if they do not use words. Families may be able to read their responses through their body language, blinks, and vocalizations to indicate yes, no, maybe. Others may use “yes/no” cards, computers, or communication books or boards.

Do your homework. Find out as much as you can about the child before you meet. Talk to a teacher, the non-offending parent, or others who know the child well. Ask how best to communicate.

Start slow.

- Communicate at a level that the child understands, based on what others have told you.

- Explain what is happening in plain, easy to understand language—but give all the same instructions or information you would give to any other child.

- Start with questions you know the answer to, such as their name or where they live, so that you can determine how the child communicates.

- Give the child extra time to process what you have said or are asking.

Clue into yours and the child’s body language.

- Keep your body language open and comfortable.

- Make eye contact as you would with any other child, but keep in mind that some children will feel uncomfortable with sustained eye contact.

- Watch for non-verbal communication that indicates understanding. This may include eye contact, gestures, posture, body movements, and tone of voice.

- Watch carefully for body language that indicates whether the child wants to talk about what happened. For example, turning away when you talk or pushing your hands away may indicate that the child does not want to continue. Making eye contact, turning their body toward you, and following your verbal directions may indicate that the child is okay with the interview continuing.

Try another method.

- If a child’s response to your questions is not clear or they don’t seem to understand, restate the question/statement in a different way.

- Use pictures or drawings. If the child has their own communication device, use that as well.

How do I go about increasing the child’s comfort in court?

Suggestions:

- Prepare children for what will happen. Bring them to court several times; when it is empty, when only the judge is in the room, and later when court is in session, to show the child that it is a serious place, with rules.

- Know how the child communicates so you can explain to the judge what type of accommodations might be needed. If you are convinced that the child would suffer undue psychological or physical harm through their involvement at the hearing or proceeding, file a motion and present the request (along with expert testimony) to the judge, who can order closed circuit TV.

- Even if the child doesn’t seem to be able to respond in court, give extra time and encouragement. Be patient.

How do I work with children who are overwhelmed, confused, or can’t remember details?

Suggestions:

- Any child can become overwhelmed, confused, or forgetful in court. Learn each child’s signs of distress by spending time with them and by asking people who know them.

- Ask what helps when the child is overwhelmed and distressed. Some children become calmer with a break, a familiar object like a blanket or stuffed animal, or a few minutes in a quiet setting. Advocate for these accommodations for that child in court.

- At a particular moment, all children can also become too distressed to continue in court. If that happens, explore alternatives. See if the judge will agree to an hour break, picking up the next day, or testifying on closed circuit TV.

- Before the trial or sentencing, decide whether to refresh the child’s memory by having them review the original interview. However, take into account that: a) the defense attorneys will likely ask in court if the child had recently seen the video, and b) watching the interview can re-traumatize the child. Prosecutors must also be careful not to appear that they want a child to testify a certain way, but rather to tell the truth at all times. Sometimes the trial is a year or year and a half year later than the original interview and outcry. Having the child watch their own video statement can serve to refresh their memory about what they remembered closer to the time of making the outcry.