How Do I Respond to Known or Suspected Abuse?

How you respond when you know or suspect a child with a disability is experiencing abuse can impact both the child's recovery and the possible criminal case.

If I Suspect Abuse

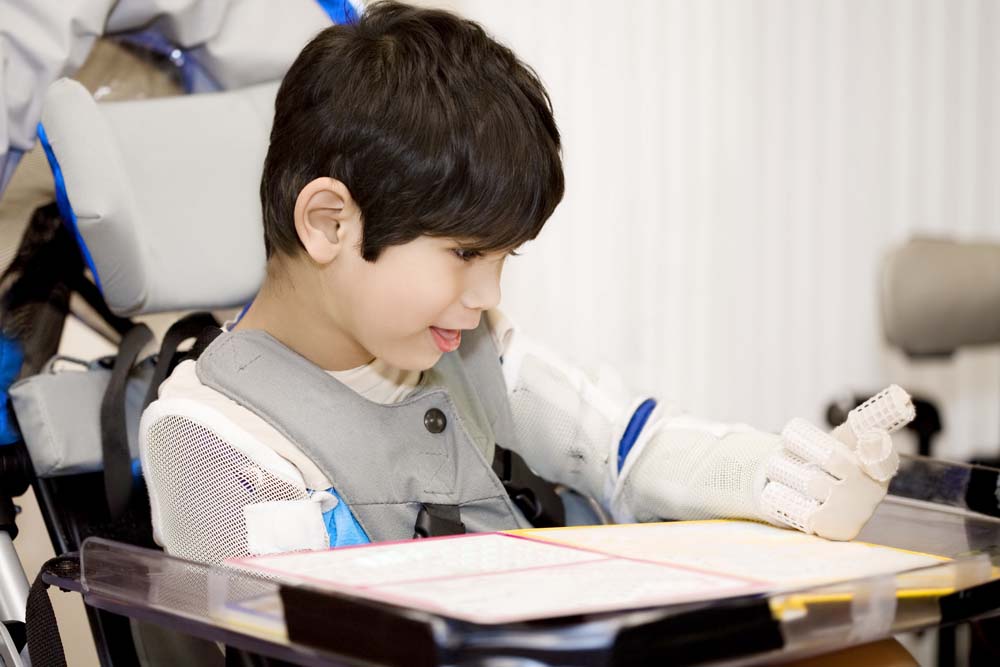

Some children with disabilities, especially significant disabilities, intellectual disabilities, or communication disabilities, may not be able to disclose abuse using spoken language. Others may not have the vocabulary to disclose or will choose not to disclose abuse because of fear, protection of the abuser, or not understanding that what is happening to them is abuse.

Some children with disabilities, especially significant disabilities, intellectual disabilities, or communication disabilities, may not be able to disclose abuse using spoken language. Others may not have the vocabulary to disclose or will choose not to disclose abuse because of fear, protection of the abuser, or not understanding that what is happening to them is abuse.

If a child in your care has a physical injury that can’t be explained or significant behavior changes that concern you, talk to them.

- Tell the child what you noticed and that you want to ask what happened.

- Keep the conversation calm, relaxed, and as casual as you can.

- Avoid pushing for information if the child doesn’t want to or is unable to talk.

- Avoid asking “leading” questions, which can make children respond a certain way. Examples: “Did Mary hit you?” “Did your brother hurt you?” Neutral questions could include, “You have a bruise on your face. Can you tell me what happened?”

- Let the child know that they are not at fault if someone hurt them, and that they aren’t in trouble.

- Tell the child you care about their safety and want to know what’s going on so you can help make sure they are safe. Whatever the child’s age, reassure them that they are safe right now and that you will do what you can to help keep them safe.

- If you are not sure how to talk to the child about your concerns, you can call for guidance to the 24-hour Childhelp National Abuse Hotline at 1-800-4-A-CHILD (1-800-422-4453)

(Adapted in part from SAFE & Crosson-Tower)

Children may not even describe it as abuse. They may describe it as something that happened as an everyday event in their life. This is part of their life.”—Tim Cromie, Sergeant Detective, Dickinson Police Department,

Texas

If a Child Reveals Abuse

Children are often afraid that by disclosing abuse to parents or caregivers, they will upset you or other people. Sometimes, they may tell part of what happened to test how you will react. How adults respond will affect what information the child shares now and later.

Remain calm and listen. If you show your anger, shock, or distress, the child may think you are upset at them. They may stop telling you what happened, or change their story to protect the abuser and everybody else. React in a way that shows concern, but also shows warmth and acceptance toward the child.

Although it may be difficult, pay careful attention to your body language and voice. Avoid standing over the child with your arms crossed. Get down to their level or lower. Use a casual, nonthreatening tone. Slow your speech.

As much as possible, hold your emotional distress until you are by yourself or with another adult.

Believe. According to criminal justice staff, one of the biggest mistakes people make is not believing children when they originally disclose abuse. Although children may not know that what happened to them is wrong, they rarely lie about abuse.

Children also react to abuse in different ways, and a reaction that seems odd to an adult does not mean the child is not telling the truth. For example, they may tell about their experience without showing any emotion.

Believing the child may also be hard to do if the alleged abuser is a partner/spouse, family member, friend, or a colleague. Nobody wants to believe that someone they care about would harm a child.

However, if you question the truth of what they are saying or blame them in any way, children may be further harmed and may stop telling you the truth.

Avoid any statement or question that conveys disbelief, such as “Are you sure?” “Really? He wouldn’t do something like that…” or “Did this really happen?”—Lindsey Jordan, LMSW, Children's Advocacy Centers of Texas

Limit questions. Let the child use his or her own words, drawings, or gestures to tell you what happened, but leave the questioning to the professionals. Repeating the story may re-traumatize children. When adults probe for more details, it may make what they remember less accurate. Additionally, the more questions you ask, the more the child may start trying to please you with their answers.

Again, avoid asking leading questions or trying to influence the child’s answers. If you ask, “Uncle Bob hurt you, didn’t he?” the child may think you want them to say yes. If you ask, “Can you tell me how you got this bruise?” they may feel less pressured in how they respond.

Also avoid “why” questions—it can make the child feel blamed or responsible for what happened.

Assure the child they did the right thing by telling you what happened. Children are often unsure about whether to disclose the abuse. They may fear that they will upset others, that they won’t be believed, or that they will get get in trouble.

Do not blame the child. Sometimes the person doing the abuse is the other parent, a close family member or friend, or someone you work with. News of this abuse may change your relationship with someone you care about. It is still not the child’s fault.

Tell the child it’s not their fault. Children often believe that not only was the abuse their fault, but that they will be blamed. The child or youth may tell you that they “participated” in the sexual abuse. It’s still not their fault. The person who exploited or hurt them is the one who did something wrong.

Don’t make promises. Some promises are not in your power to control. Adults naturally want to reassure children that the abuse will never happen again and that they will keep them safe. Sometimes this is just not possible. If it does happen again or the child is not safe, they may lose trust in you.

Be honest about what you are going to do next. Do let the child know that you will need to report the abuse and that what the abuser did was not okay. It’s okay to say you don’t know what is going to happen, but that you will be working to protect and keep them as safe as possible. Children who love their abuser may feel very guilty about disclosing abuse, as well as ashamed of being abused. Others may be afraid of what the abuser will do in retaliation.

The more the child gets interviewed about their situation, the more trauma gets imposed in their lives because they have to relive it. People want to know what happened to the child, and who better than the child can tell them? But asking more details can really hurt their child, and the interviewing should be left up to trained professionals who are able to elicit detailed information of the abuse.”—Mikey Betancourt, Executive Director, Children’s Alliance of South Texas ~ A Child Advocacy Center

What to Do Next

Write down what you remember. After you talk, write down what the child said as accurately as you can, so you can share it with investigators. If the child did not or cannot disclose abuse, write down what you noticed and why you are concerned.

Report the abuse or your suspicions of abuse. Often, people don’t report abuse to Child Protective Services or law enforcement out of fear that they do not have enough information to report. However, in Texas, it is a legal requirement for all citizens to report any known or suspected abuse against a child.

Work to keep the child safe. If the child is afraid of punishment because the abuser is a member of the family, and if you are concerned the child is in immediate danger, call the police. Work with Child Protective Services or the police to keep the child safe from the person who hurt them. If they will still have contact with the abuser, work with others to develop a safety plan appropriate to their age.

Address emotional safety. Seek help and support for the child who has been abused as well as the rest of the family. If you are a parent, the child may want to sleep with you, sleep with the light on, not go to school for a day or two. They may not want you to share what they said to other family members, friends, or teachers. Let the child know who you will need to tell, and why. Be as careful of their privacy as you can.

A child who is not able to disclose abuse and is confused about why things are suddenly changing in their world will need comfort too.

Know that a child’s story can change over time. This is especially true if the child has experienced years of abuse or neglect. Trauma impacts memories for both children and adults. Every child’s memory is different, and some children remember more over time. In addition, children may disclose more details after they have tested whether it is safe to disclose.

Also know that children frequently disclose abuse and then try to take it back. Children may recant, or take back what they originally said, because they want their family life to return to normal, they don’t want to see everyone upset any more, or they want their abusing parent to be able to come home. When children try to take back their disclosure, it does NOT usually mean the abuse didn’t happen.

Address the child’s feelings of shame and blame. Much of the time, children are abused by someone they know. After the child discloses abuse, the family may lose income, stability, or contact with other family members. Children will often feel responsible for these changes. That feeling can easily be reinforced by other children, family members, and parents. Continue to reassure the child that it’s not their fault and that they did the right thing by telling you what happened.

Be careful who you talk to about the case. The people you talk to may end up being witnesses that child abuse investigators need to talk to.

If the child loves the abuser, be neutral. If you threaten the person or talk bad about them, the child may feel guilty or protective and take back their disclosure. If the child does not want to be separated from the abuser, explain that what happened wasn’t okay. One way to explain this is to say that the person did something wrong, and needs help.

Get support. This child was impacted by the abuse and so were you. You are likely to be full of many strong emotions: Fear, outrage, anger, sadness, guilt, shame, and other confusing or ambivalent feelings. If you are a parent, seek counseling or other support for yourself, the child, and other family members.

(The material in this section was compiled, in part, from personal communications with Mikey Betancourt, Executive Director, Children’s Alliance of South Texas – A Child Advocacy Center; Tim Cromie, Sergeant Detective, Dickinson Police Department; Lindsey Jordan, LMSW, Children's Advocacy Centers of Texas; Anna Phillips, Education Specialist, Region 17 Education Service Center; and Dr. David Scott, University of Texas at Tyler, Department of Social Sciences. It also includes information from SAFE; The Mama Bear Effect, Stop it Now, RAINN, & ChildHelp.)